|

They emerged in the early 1970s wearing intergalactic glam garb, offering avant-gardish paeans to Bogart and beauty queens, among other things; 10 years and several unclassifiable records later (Was it art-rock? Lounge music from a forgotten future?), Avalon saw them out as polite pop sophisticates. Singer and main songwriter Bryan Ferry’s debonair persona was the one constant, and it spurred his solo career even before Roxy disbanded. It’s hard to explain Roxy Music, as they blend a rock essence with pop-art elements (they were an early example of postmodernism), and the gradual move toward smooth romanticism further confuses things. The underlying musical basis - Ferry’s four-chord tunes with personal lyrics - remains pretty much the same, though; only the settings and decoration change. Lieutenants Andy MacKay (saxophones, oboe) and Phil Manzanera (guitar) provide a variety of instrumental interest. Drummer Paul Thompson’s earthiness grounds everything up through Manifesto. Various bassists come and go - Roxy never had a permanent one. And then there’s Brian Eno, whose synthesizer and instrument treatments give the first two albums an otherworldly sound and hipster status. In 1973, Eno was nudged out by Ferry’s domination. Some of the intellectual atmosphere left with him, replaced by a decadent haute couture of fine musicianship, figurative palm fronds and champagne bottles, tuxedos and forced-grin females. It’s the meeting place of rock sensuality and the cufflinked classy life that Ferry pouts about in his lyrics.

The individual RM albums are available as Virgin remasters.

The best comment on the debut came from Brian Eno, who said something to the effect that it had about a dozen possible futures on it. This implies that the tracks aren’t so much songs as artifacts, or system theories, and it’s as truly arty as they ever were. There’s a rock thrust from guitarist Phil Manzanera, drummer Paul Thompson, and bassist Graham Simpson, tweaked by Andy MacKay’s reed work (honking sax, twittering oboe), and manipulated into a spacy haze by Eno’s sonic necromancy. In the midst of it all is Bryan Ferry’s eclectic songwriting, which he voices in a schizoid gamut from lounge parody (“2 H.B.”, “Bitters End”) to wicked bard. Rock indeed gets warped on this album, more from a conceptual standpoint than the playing. The best tracks rely on structural juxtaposition, such as the journey “If There Is Something” takes from bent country to a dark motivic section (with an outstanding sax solo) to a grand denouement. Or the melding of various elements in “Ladytron”: solemn oboe, another C&W verse, and a furious finale with Eno processing Manzanera’s guitar into alien shards. Both tracks are among Roxy’s all-time best. I’m not a fan of forced eclecticism in rock bands - here’s some crunch, here’s some reggae, here’s some jokey swing - but somehow Roxy makes it work, perhaps because there is a theoretical artifice to it. (Such as the instrumental bites at the end of “Remake/Remodel” - Wagner, wacky synth, etc.) The crazy quilting reaches a head in “The Bob (Medley)”, a five-panel suite of hard rock, chamber passages, a ‘60s pop episode, and a synthesized aerial raid (BOB = Battle of Britain). The band’s other ace is a radical superimposition of ideas, best exemplified by the nearly atonal feedback guitar that infects the intimate “Chance Meeting”. Ferry’s broken vocal delivery in that song is interesting too, as he acts out the lyric’s awkward subject. In the nostalgic yet futuristic “2 H.B.”, Ferry’s naked ode to an atmosphere of yore slides into a graceful tableau of electric piano, subtle drumming, and an echo-bed of sax phrases. “Sea Breezes” would be on the same level except that the release point in the middle (after a couple of downcast verses) is sabotaged by a stumbling rhythm and errant bass notes - a case of deconstructing things to a fault. (Ferry offered a “straighter” rendition of this song on his solo album Let’s Stick Together, which I prefer. He also redid a couple of others from this record.) Elsewhere are some plain weird pieces, like “Remake/Remodel”, a quirky, primal rocker where Ferry pines for an object (girl? car? biomech hybrid?) he didn’t have the nerve to approach. The throwback ‘50s sound of “Would You Believe” is too kitschy for its own good, and the bridge contains Ferry’s most irritating singing on record. It’s hard to complain about “Bitters End” because it’s just so bizarre - a couple minutes of ornate whimsy with a lyric you have to peruse twice. The CD remaster also contains the single “Virginia Plain”, a pre-new-wave song that everyone deems a classic but which frankly bores me. Bare-minimum rock, it goes by quick.

In all, Roxy Music moves forward, backward, and sideways. “Ladytron”, “If There Is Something”, and “2 H.B.” are classics of the time. Most of the rest of the album is intriguing, and it will shock anyone backtracking from Roxy’s smoother future.

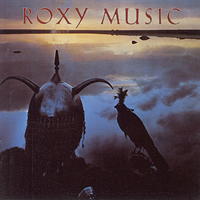

For Your Pleasure is even stronger across the board, from Ferry’s bold vocals to the road-muscled playing. The creepy midnight of the cover art invades all of the tracks, whether urban-flavored (“Do the Strand”, “The Bogus Man”) or rural (“Beauty Queen”, “Grey Lagoons”). Ferry doesn’t really write verse-chorus structures, so the band is left to their own devices for arrangements, and Eno’s ghostly treatments thicken the uncertainty. “Do the Strand”: How ostentatious to not only create your own (fake) dance craze, but to namedrop the hell out of the lyrics, and to give the music some dark turns. At exactly four minutes, “Do the Strand” is jam-packed with information, and by the time Ferry announces “They’re playing our tune,” it begins to make sense. Good kickoff and a live favorite. “Beauty Queen”: Ferry’s shuddering electric piano and personal vocal take center stage, backed by a cool rhythm, and Manzanera’s mid-song diversion rocks out. “Strictly Confidential”: Another vocal outpouring, Ferry in anguished self-conversation over a doomy minor key. Stage right and left, Manzanera and MacKay provide stinging counterpoint (almost in the vein of “Chance Meeting”), and Thompson adds skeletal drums. My least favorite on the album, it’s a bit overbearing without much reward. “Editions of You”: And the dense lyrics keep on coming. Ferry dispatches an observation about “modern ways” over a catchy three-chord keyboard riff. It’s a straightforward charge all the way through, one of the few Roxy tunes from this era that doesn’t divert itself. The group pounds away, and solos from sax, synth, and guitar let Ferry catch his breath. “In Every Dream Home a Heartache”: Over a spooky backdrop, Ferry speaks a monologue about a deadened life; despite “deluxe and delightful” surroundings, the protagonist is reduced to wooing an inflatable doll, which ends up blowing his mind and releasing a guitar-howling cacophony. Drama doesn’t come more obvious than this - suspenseful setup, full-bore blowout - but neither could this drama have come from any other group. The non-stop four-chord cycle is so simple yet theatrical, and how about that twisted organ (?) sound? How about the balls it takes Ferry to plant himself right up close and say these things? I know it’s just perverted art rock, but in the right frame of mind, it’s damn unsettling. “The Bogus Man”: Initiating the second half of the album, “Bogus Man” is the most uninterrupted “jam” to be found in Roxy. It goes from a couple of verses about a dangerous figure of some sort (made even creepier by the soft falsetto delivery) into a long, funky, textural improvisation, where guitars bat about and MacKay blows a serial style of avant-sax. Ferry plays sinister wah-piano and the beat variations from Thompson and bassist John Porter are excellent. Eno, one presumes, contributes to the delays and altered timbres of the instruments. Without traditional solos, it’s more of a sensual mise-en-scene minus foreground actors. I really dig it. “Grey Lagoons”: As the bogus man shuffles away, the croony throwback vocals of this song come as quite a shock. It’s a far better pastiche than “Would You Believe”. The rhythm, for one, is much funkier, the main vocal melody is attractive, and there’s a good sequence of solos where Ferry tosses in some harmonica. “For Your Pleasure”: A haunting piece to close the album. Ferry delivers a mature vocal atop a mysterioso backdrop of simple gestures turned weird in Eno’s sonic clouds. The solemn verses eventually herald a vast “ta-ra” of seesawing chords and isolated lines, wobbled by tape delay and borne on Thompson’s processional tom patterns, all receding into the night. For mood, style, and substance, this is a Roxy pinnacle.

All of the above makes a masterpiece. It marked the end of Eno’s tenure, the best move for both parties in hindsight.

Into Eno’s vacancy comes Eddie Jobson, a violin/keyboard whiz kid who ups the face-value musicianship of the group. Meanwhile, Bryan Ferry reigns supreme on a cushion of lush sound. This is where he really starts to front his high-class persona, and where the surrounding instruments don’t intrude on his texts so much. For a long time, I didn’t like this album (apart from a couple of songs), because it lacked spikiness and seemed a little too grand. Recently, I’ve done an about face and realized that it’s just as creative as any of the nearby albums, though everything stands or falls on those daring vocals. May as well do another track-by-track. “Street Life”: The rolling rock background is good, as is the confined dissonance of the instrumental refrain, but I don’t buy the pompous vocal. Sort of an imported Motown feel to this tune. “Just Like You”: Ferry had cut his first album of covers before recording Stranded, and “Just Like You” nods to the old standard style. When I first heard it years ago, it represented everything I didn’t like about Stranded, but maybe I was stuck on the tweeness of the opening verses. Truth is, it’s a good vocal performance. Manzanera contributes a nice solo and the track ends on a surprising chord, almost like it’s hinting at how schmaltzy it could have been. “Amazona”: Co-credited to Manzanera, who probably wrote the rhythm riff and the asymmetrical “falling” interlude. Had this been an instrumental topped with MacKay extemporizing, it would be excellent. But Ferry instead throws a useless vocal over the top (singers abhor a vacuum, you know), and weirdo processing overwhelms the track midway through. Apropos Eno, the group wanted to maintain some of the sonic FX, but in “Amazona”, it’s done to a fault, warping the instruments into unidentifiable strands. Nevertheless, you still get an earful of fine English funk. “Psalm”: The sincerity of the spiritual lyric is disarming, as is some of the passion in Ferry’s voice. Yet there are enough mild stingers in this gospel-inflected crescendo to make one think twice. Paul Thompson’s hobbling drum groove (very New Orleans) and Manzanera’s sideline licks are of sinner’s flesh, while an actual choir is buried in the mix like an eerie Mellotron. A church-style organ runs throughout, and near the end, MacKay improvises on soprano sax alongside Ferry’s “forever more” deliverance. There’s a slight tension to the whole picture, where one facet counters another, and thus it’s pretty interesting. The only real problem with “Psalm” is that it goes on too long, and the extreme vibrato that Ferry sometimes uses is surely not to everyone’s taste. “Serenade”: This quick tune is fairly bombastic on the surface but it has some crafty substance underneath. Over the booming rhythm and saturated layers of guitar and keyboards, Ferry serenades his subject with self-assurance. (“Will you swoon, as I croon?”) The harmonic tone is very consonant, and there’s a neat country-ish chord turnaround, too. I think it’s clever how the end comes out of nowhere to replay the same musical phrase that began the song. “A Song for Europe”: A Ferry-MacKay collaboration with very stately music. Ferry issues one of his most melodramatic vocals yet, where you can see the cigarette smoke and the white tux and sprawl of cinematic imagery as he wallows in the depths of solitary reflection. Meanwhile, the featured sax solo wails all those emotions that words cannot express. It’s all too heavy for me, too obvious. Once you know where it’s going, there’s no payoff, just repetition. And half-ass French. “Mother of Pearl”: The opening minutes feature a hectic rock riff with multiple vocals that depict a partying scene of some sort, and then everything cuts away to a piano vamp and a lengthy Ferry rant of post-party introspection. In the stream of consciousness lyric, Ferry pines for that one mythical other, while the vamp is decorated with pinging guitar, droning sax, percussion, and more. Thompson and bassist John Gustafson lay a slick groove underneath it all. This is without question one of the best pieces in the Roxy catalog, an equal mix of the “arty” and the romantic. “Sunset”: Piano and bowed bass trace unusual chord movement under a quiet yet commanding vocal; in the middle, a trickling piano figure provides the sweet side of bittersweet. Understated and tasteful, “Sunset” brings the album to a beautiful close.

Stranded has always been highly touted, even by Brian Eno. I think it has a positive vibe and some original music, but Ferry doesn’t always live up to the lofty air he assumes.

The only time I won’t say this is Roxy’s best album is when For Your Pleasure is spinning, and even then it’s a toss up. Country Life reasserts the group’s stridency, mainly thanks to Manzanera’s guitars, and it refines the romantic pastures of the preceding disc. Ferry’s in good form. Bassist John Gustafson sticks around for this album and will for the next one, too. No attempt is made to retain the warped, Enossified style; the group instead focuses on being a versatile rock band. “The Thrill of It All”: A remade/remodeled piano riff introduces a juggernaut with propulsive rhythm, agitated strings, churning keys and guitars - a soundstage so crowded that barely any room is left for Ferry’s somewhat apocalyptic emceeing. (Whatever party he’s at, I’d like to stop by for a drink.) A couple of detours put pause in the relentless assault. Great opener. “Three and Nine”: In contrast (and Country Life is all about contrast), here’s a lighter diversion featuring key phrases from MacKay and a whimsical lyric. “All I Want Is You”: Guitars roil and rake all over this edgy pop rocker. Viva Manzanera. A simple song with grand impact. “Out of the Blue”: There’s a lurching main theme for oboe, a couple of doomy verses, only one chorus (a bright invocation of the title), and a stunning violin solo in the homestretch. Since the first half of the seventies was a time for flaunted musicianship in rock, “Out of the Blue” nods in that direction yet retains a compact form. “If It Takes All Night”: Has anyone ever noticed that this countrified blues tune has a nine-bar structure? The performance is straightforward and fun, carried by a helpful bassline. “Bitter Sweet”: If you mix the heavy melancholy of “Song for Europe” with a stage musical approach, you get this bizarre mini-suite, replete with goose-stepping chorus line. The sheer nerve of this piece sells it, and the clangorous guitar in the bridges is a nasty treat. Late evidence of Roxy’s art-rock chutzpah. “Triptych”: Equally bizarre, this short piece has a medieval tone, and Ferry summons religious imagery with no outward irony. It feels out of place on the album - it would feel out of place on any album - though the final section is nice. “Casanova”: Resuming the album’s hard rock feel, “Casanova” has a gritty funk beat, clavinet (yes sir), nasty guitar, and a venomous lyric in which Ferry insults some intoxicated, womanizing character. Er, self-flagellation on Bryan’s part, or what? No chorus, no forgiveness, just a grinding plod with shrapnel falling left and right. “A Really Good Time”: In which Ferry re-imagines himself as a standards singer, telling off some floozy. Friendly piano and strings are offset by a tougher recurring motif. I wouldn’t want a whole album’s worth of songs like this, but “A Really Good Time” earns its place after all the thorny tracks that precede it. “Prairie Rose”: The opening guitar chords suggest ominous importance, which the ensuing full-band climax does nothing to dispel, then the verses open into a great expanse to fit the lyrical invocation of Texas - “what a state to be in.” The energized country life comes into full view on this track, interrupted by batter-splattering solos from sax and guitar, and driven to an extended coda with a rousing countermelody. “Prairie Rose” might well be my favorite RM track ever, and it’s a fine way to send out this LP.

The steelier components of Country Life lead some people to call it Roxy’s “rock album.” (As opposed to what? Pop? Disco?) It’s actually a grab bag of different styles bound together in what I think is their most satisfying program.

Things start to hollow out a bit on Siren, and the clouds of mystery begin to lift. Having shocked and experimented and wooed, perhaps all Roxy could do from now on was entertain. Feed the machine - ah, but they do it so well when they try. For one, there’s the rightly popular “Love Is the Drug”, a strutting funk number fueled by The Great Paul Thompson. “Both Ends Burning” is equally classic, a groove machine swathed in synth strings and voiced by Ferry at his best. The midtempo “Nightingale” takes an easygoing, emotional flight on guitar breezes, and “End of the Line” continues the sporadic Roxy tradition of the amiable country and western tune, doused with teary-beer fiddling and a background slide guitar. No complaints about these four tracks, which are worth the price of admission. The remaining cuts are just as enjoyable in many ways but contain some questionable moments and/or a milking of minimal ideas. The galactic soundscape of electric piano, fuzz guitar, and oboe that opens “Sentimental Fool” is fantastic, and the darkened homestretch is also very cool (love the fake ending), yet the verses in the middle are too sing-song elementary. “Just Another High” - which delivers lyrical justice to the club-crawling player of “Love is the Drug” - has a reserved majesty yet is saddled with an overlong coda. There’s no denying the energy with which the band unleashes “Whirlwind”, but the song itself is an impatient retread of “Prairie Rose” that means little. The schizoid “She Sells”, co-written with Eddie Jobson, hops from one outpost to the next, including a segment that sounds exactly like Zeppelin’s “Trampled Underfoot”. Partway though, it lurches into a different tempo altogether.

The one really banal track is “Could It Happen To Me”. Not a bad song per se, it gets a foothold on the idea that Roxy could simply revolve around Ferry’s persona and nothing more. Regardless, the running order of Siren minimizes any “warning signs” by keeping the best cuts evenly spaced, and it adds up to a pretty good record. Surely the group was sensitive to diminishing returns, though, because Siren was the last effort before an indefinite hiatus.

Eight tracks culled from different concert rounds, featuring ex-Crimsonite John Wetton in the bass slot. He’s a perfect fit for Roxy’s heavy sound of this time, where tunes like “Out of the Blue”, “The Bogus Man”, and “Dream Home” come loaded and swaggering. Manzanera’s guitar stands out, as does MacKay’s streaking sax, and Jobson has two solo spots. Ferry loves preaching to a converted audience, as can be heard in the expansive, multi-soloed rendition of “If There Is Something”. (I can’t say if I like this or the studio portrait better.) The 1973 single “Pyjamarama” is done up in tough guitars and wah-keyboard, while “Do the Strand” and “Both Ends Burning” work well live. The latter, however, contains the ludicrous backup vocals of the Sirens, a couple of female lookers who were hired for reasons other than, like, knowing what notes are. Anyway, Viva has its share of power and drama.

The return of Roxy follows a) Bryan Ferry having furthered his solo career, and b) the blossoming of rock’s new wave (partly inspired by old RM). You can guess the result - everything’s slimmer and more transparent. Jobson’s gone; Gary Tibbs and Alan Spenner swap bass duties; and keyboardist Paul Carrack joins. Of the four principals, Manzanera and MacKay tone down their idiosyncratic styles, and Paul Thompson is relegated to unvarying beats. Ferry, front and center, doesn’t always sound enthusiastic. There’s little evidence of this group needing to work together again; in fact, most of the album is quite perfunctory. It gets off to a promising start with the title track, which builds up a portentous prelude to Ferry’s vocal (over continually modulating chords) and concludes with eerie clouds. If the lyrics were better, I could endorse it fully. Later on, the group goes into “Bogus Man” mode in the spacy funkscape of “Stronger Through the Years”, filled with great bass work, synths, and avant-sax. Most of the rest is tidy pop-rock that coasts on one genre or another, like the noir-soul of “Ain’t That So” or the ambling “My Little Girl”. Both of these songs, tellingly, have cheese-whiz backing vocals. The self-descriptive “Trash” hops on the post-punk train, replete with tinny organ and idiot rhythms, mercifully ending after a couple of minutes. The Jekyll-Hyde duality of “Still Falls the Rain” is kind of fun, but the nice verses give way to a moronic vocal in the chorus. “Angel Eyes” is a guitar-heavy charger with a couple of snaky instrumental breaks; the album version is different than the dance flavored remake found on the greatest hits discs. “Cry Cry Cry” is an awful sub-Stax anomaly that I vote the most artistically offensive RM song to date. (Given a run for its money by “Trash”.) The three-chord lullaby “Spin Me Round”, poignant though it is, may as well have been on any Ferry solo album.

And then there’s “Dance Away”, a successful distillation of Ferry’s classic pop tendencies, dressed up with a seductive beat and measured instrumentation. It’s a double-edged sword: the track is enjoyable in itself yet it paves the way for more of this middle of the road attitude. In fact, most of Manifesto marks a sea change from the craggy Roxy past. Overall, a very uneven, unconvincing LP, and the cruel truth is that even the better tracks are disposable.

Alternate Ending #1: Go totally bland and plastic. Press out and lint roll the music like an evening suit. Replace the drummer with someone slicker. Hire a second guitarist. (?!) Record a couple of tranquilized covers. Write repetitive songs. Throw a couple of bones to Manzanera and MacKay, but also record one track without either of them.

Flesh and Blood is superficially more resonant than Manifesto, as if the latter’s ragged menu permitted the band to make a decision on where to settle. Well, forget “band,” this is Ferry’s vision, and he settles into a luxurious pop/soul chamber where everything flows evenly, give or take a couple of moody textures, as on the title track and “No Strange Delight”. My favorite track - just for the Anglo-funk of it - is “Same Old Scene”, a neo-disco number bound up in Manzanera’s delay repeats. “My Only Love” has a somnambulant appeal, despite repetition of a thin premise. I have to credit “Oh Yeah” as well-written confection, although it like several other tunes from this time should have gone on a Ferry solo record. “Over You” is whitewashed simpleton pop with only a small guitar break having remote Roxy flavor. And egads, what’s with the musical Valium of “Midnight Hour” and “Eight Miles High”? If you’re in the mood for smoove grooves, or if you’re just a Ferry fan, this isn’t a bad record. Neither could it be confused for a great one.

Alternate Ending #2: Render the background so slick and subdued it’s hardly noticeable. Conjoin keyboards, ethereal guitar, and sax in a pop moonlight sonata. Go, in effect, for pure ambience. Make a great record despite being as dysfunctional as ever. Avalon succeeds by equalizing everything, even the vocals, in a thick atmosphere. In other words, if you want moody romanticism, best to emphasize mood, which all of the songs and arrangements do. Funnily enough, it sort of goes full circle back to the first two albums, which had the spooky aura courtesy of Eno. Here, Ferry (who plays tasteful keyboards), Manzanera, and MacKay drift in their own soundworld, spiced up by percussion and a few snazzy bass ‘n drum carpets. The lightly dancing title track is one of Ferry’s most endearing efforts, and it’s just evocative enough to fit under the Roxy moniker, too. “More Than This” and “Take a Chance on Me” are both airy pop with classy instrumental gilding, while “The Main Thing” drapes the album’s funkiest rhythm in incidental uncertainty - spectral synth pads, pithy guitar warnings, etc. All of the tracks (two of them are short instrumentals) fit into an even-keeled suite. Sure, the aggression of the past is long gone, but they finally replaced it with something affecting if not totally substantial.

Even though Ferry’s vocals recede into the mix, he still reigns by suggestion, and there’s yet another track (“To Turn You On”, lovely in itself) without Phil or Andy. Avalon’s unified sound belies the fact that the group, such as it remained, was breaking up for real this time.

Roxy Music succumbed to the reunion bug in 2001, as lengthy absence had apparently made the hearts of Ferry, Manzanera, and MacKay grow fonder of their chapter in British rock history. Augmented by a crack supporting cast, including original sticksman Paul Thompson (who makes so many of these tunes feel good), they toured the happy theaters with an unapologetic celebration of their past. Instead of “promoting” an album or needing the bucks, the group’s main motivation was an enthusiasm for their catalog, which spills over into this fine two-disc set. (Tracks come from various gigs.) No scrimping on the early stuff either, as “Virginia Plain”, “Ladytron”, “Out of the Blue”, and others are faithfully resurrected, right down to the primitive synth effects that a certain Eno contributed back in the day. Ferry’s recitative “In Every Dream Home a Heartache” remains a chilling bit of psychosis, and “If There Is Something” is an inspired choice, even if it misses some of the gravitas of old. The music barely shows its age, which may have something to do with Ferry’s best writing never being completely indebted to any faddish genre. The later material works well, too, like punchy updates on “More Than This” and the Manzanera spotlight “While My Heart Is Still Beating”. The beautiful “Tara” adds Lucy Wilkins’ soaring violin to Andy MacKay’s original soprano sax soliloquy. Communion occurs in “Mother of Pearl”, arguably the highlight, and thank goodness for Paul Thompson’s sturdy grooves, that’s all I can say. Closing the set is “For Your Pleasure”, a perfect choice as it allows the band members to leave one by one during the spacy finale. You’ll find a few down moments as well, like the overbearing extension of “My Only Love”, but in the main, this is a pretty strong collection.

The companion DVD Live at the Apollo is well worth it for Roxy fans. The sound and picture are fantastic.

|