|

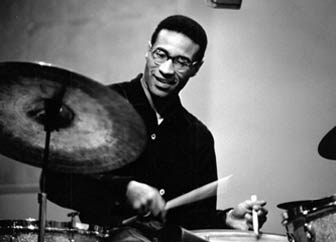

A quintessential jazz drummer, Max’s role in the development of bebop shouldn’t be underestimated, nor should his creative accomplishments, like the bands co-led with Clifford Brown, the countless sideman appearances, his percussion ensemble M’Boom, and later adventures with the likes of Anthony Braxton and Cecil Taylor.

Max’s swing is right on top of the beat, his stickwork is precise, and his fills have musical purpose. He demonstrated that the drums could be just as involved musically with a given tune as any other instrument.

The Brown/Roach quartet embodied straight hardbop at its most aggressive, complex, and thrilling. Clifford Brown was a stunning trumpeter, able to craft melodically sound lines at a fast clip. He took the next step on from Dizzy, and there’s no telling where he would have gone had he not met his early demise in 1956. Apart from Brown’s awesome technique, his melodic sense was something else. So many of his phrases are perfectly self-sufficient when isolated from the high-speed contexts in which they emerged. Personally, I learned about playing ii-V changes from his exemplary “Pent-Up House” solo with Sonny Rollins. Also at this time, Max Roach was making the step from capable sideman to quintet co-leader. For this band, Brownie and Roach recruited the lean tenor Harold Land, pianist Richie Powell, and bassist George Morrow. Along with being one of the most invigorating albums from the 1950s, this is in my opinion the best of the Brown/Roach catalog. The upbeat themes “Daahoud”, “Parisian Thoroughfare”, “Joy Spring”, and “The Blues Walk” are each complex yet have appealing hooks. Brown’s “Joy Spring” starts with a moody fanfare and then unwinds a long line of modulated elation, while “Daahoud” puts a fresh shine on bebop. Singling out solos from these tracks is silly - all of them are good, with Brown’s effortless virtuosity, Land’s winding sax, and Max’s breaks. The contributions of Powell and Morrow are important too, even though they don’t stand out as much as the others. (Not counting the piano trio spotlight in “These Foolish Things”.) And listen for the few bars of 5/4 in “What Am I Here For”, a little Roach touch, surely.

With their out-front technique and precise teamwork, the quintet usually avoids anything impressionistic, but “Delilah” opens with a quiet vamp as seductive as anything the soon-to-be Miles quintet would come up with. The solos on the tune are laid back as well, even Roach’s muted rolls, so the band doesn’t always have to blaze the guns in 4/4. The 2000 edition from Verve adds three alternate takes and has wide dynamic range for a mid-50s recording, from the hushed “Delilah” to the full throttle “Parisian Thoroughfare”. An essential item with timeless contents.

Max joins avant-garde multi-reedist Anthony Braxton for a freely improvised live performance that benefits both men: outsider Braxton gets to play with one of jazz’s biggest insiders, and Roach has the chance to break genre boundaries. Braxton plays alto, soprano, sopranino, flute, clarinet, and contrabass clarinet, while Max occasionally steps away from the trapset to access chimes, tuned cymbals, and gongs. Along with the instrumental variety, the key to this successful meeting is the differing means of communication. The first half of the concert is concerned mainly with contrasting textures, such as the high soprano to the low toms, or Max’s ringing metals versus Anthony’s growling bass clarinet, a must hear in itself. The second half is more about exchanges. Both Braxton and Roach get extended solos, with or without support from each other, and the concert ends with quick Q&As between sopranino and toms. (Call and response is the first thing you’d expect an improvising duo to explore, but it’s one of the last resorts for these two.) One of the more exciting sequences is when Max starts an extended rendition of his snazzy solo piece “Self Portrait” and Braxton improvises on top of it. There are also stretches of pure swing where the outsider does a good job of keeping up with the insider.

There are so many cool examples of Roach’s drumming here, from the multitude of rhythms to the sharp cracks of his snare. Despite a few abrasive tones from Braxton, it’s a very accessible free jazz suite and logical enough to follow. It’s very apparent which means of communication the players are employing at any given moment - either contrast or exchange - and Braxton is good at mimicking Roach’s rhythmic ideas and establishing melodies at the same time. Fans of one or both musicians must track this album down, especially those Roach listeners who haven’t yet followed their man past the bebop domain.

On most other albums, Max plays drums, but on this occasion, he calls them a “multiple percussion set.” The nominal elevation is due to the jazz/classical hybrid “Survivors”, a 21-minute piece (arranged by Peter Phillips) that mixes lacerating string passages with a constant barrage of drumming. There’s a nifty bit where Max gets his tom rolls to waver in pitch while playing with both hands. Impressive and precise as “Survivors” may be, the fragmented string parts and the dry instrumental match make for a taxing listen. A cup of strong coffee is almost a prerequisite to listening, and it certainly required intense focus on the part of the players.

The second half of the album features Max alone playing six tune-like drum solos. They all state their theme between snare, hi-hat, and kick drum, after which Max improvises and then restates the theme. He goes a long way in demonstrating the musicality of the drums, extracting wide variety of sound from his kit. “Self Portrait” is the definitive Max solo, I think - an off-center riff of bass drum, clamped hi-hat, and ricocheting rim shots, which then gets reversed and built to a flurrying climax. No chords, no melody, no real pitches, yet it tells a short story. “The Drum Also Waltzes” is another intelligent display of form and tension. (It’s not the only time Max recorded it, and drummer Bill Bruford did an amazing cover of the piece in 1985.) Max doesn’t try to impress with technique or force in these solos; he’s just exploring themes and variations, and anyone who’s listened to his drumming as far back as the 1950s will not be surprised by what he does here.

This 2-disc set summarizes where Max had been in recent years. The lion’s share of space is given to his quartet with Cecil Bridgewater (trumpet), Odean Pope (tenor sax), and Tyrone Brown (bass). There are also appearances by the M’Boom percussion ensemble, the Uptown String Quartet, and a vocal chorus. The music comes from both the studio and stage, all well recorded. Both discs open with an “epic” piece for expanded personnel, the first of which is the three-part “Ghost Dance”. This piece features a vocal chorus with spotlight singing by Ronnell Bey. Normally I’m not a fan of jazz vocals, but these Native American-based lyrics sound pretty hip over the bluesy, swinging music. The solos are good, too. The middle section is performed by M’Boom, who march and sparkle on an array of percussives. The other large-scale piece is “A Little Booker”, which pairs the string quartet with the regular Roach jazz quartet. At first, the strings just add classical angles, yet as the tune builds up the strings get more integrated. The extended bass/drum exchange later in the piece blows off a lot of steam. The jazz quartet gets a few tracks to itself, notably the 5/4 “Tears”, featuring Pope’s searing tenor (his split tones sound like a honking big rig). The electric basslines and terse melodies of the live “Mwalimu” are attractive, and what really stands out is how loose Max’s drumming is - he hangs as far off the beat as Jack DeJohnette might. Meanwhile, Pope generates all kinds of sax sonorities and new ensemble riffs pop up here and there. M’Boom delivers the pure percussion experience in three tracks, most enjoyably the hypnotic “A Quiet Place”, very Reichian and consonant, teeming with marimba, bells, and whatnot. At the end of both discs, Max gets a solo piece to himself, one being “Self Portrait” and the other the thundering “Drums Unlimited”.

Overall, there’s some vital music on these two discs. It’s not just a retrospective celebration, as the leader was still pushing forward. Max’s quartet had been making records throughout the 1980s for Soul Note, and their performances on this set sound at least as good, if not better.

|