|

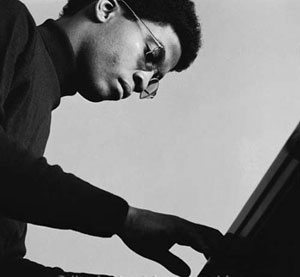

Herbie Hancock started off on piano in the real-life grad schools of the 1960s, playing straightahead and abstract jazz of the highest caliber, then turned to fusion in the 1970s and later flirted with R&B, rock, and techno. My opinion is that he made his best music early on in the jazz field, not pandering in any way, but then I’m just the schmo typing this, and he’s the one who darted from genre to genre with ease. The benefit of Hancock’s wide range is that he eventually became a household name, and he makes a better spokesman than certain others, having no truck with sanctimoniousness and narrow definitions.

Hancock’s recorded legacy is enormous. He returns to the straight jazz fold regularly, albeit with thematic concepts (like New Standard, or Gershwin’s World).

Herbie’s first calling card as a leader swings with blues-bop simplicity, not far beyond where jazz had already been. In comparison to later efforts, Takin’ Off is an artistically slight end in itself. In execution, though, the album makes a good impression, with friendly support from Dexter Gordon, Freddie Hubbard, Butch Warren, and Billy Higgins. The main flavor is found in the easy-bake blowing tunes. “Watermelon Man”, “Empty Pockets”, and “Driftin” all have declamatory blues heads, ain’t-it-happenin’ vamps from piano, and solos that play themselves. The first of them became a bona fide hit, establishing Hancock’s commercial potential early in his career. Hancock also dabbles in suggestive landscaping in “Three Bags Full”, a harmonized theme in 3. “Maze” ditches the blues crutch for an enigmatic air, with Herbie’s ambiguous voicings and solo breaks being maybe the most interesting music on the album. (Dexter’s solo is good, too.) The Bill Evans piano influence surfaces in “Alone and I”, a ballad in which Hubbard summons the sensitive spirit of Miles.

Hancock’s major trait at this point is his rhythmic vocabulary. He fully understands swing, and he also can get funky on a dime, switching between rhythms with ease. This would remain a lasting part of his identity as a player and facilitate much of the genre crossing he would do later. However, in terms of material, Takin’ Off is the most generic of the Blue Notes.

Expanding the palette a bit, with extra touches of trombone (Grachan Moncur) and guitar (Grant Green) on a handful of tunes that in hindsight are a little mannered and out of character. The leader’s creative point of view has broadened since the debut, but the compositional voice is still in progress. The gauzy melodic artifice of “A Tribute to Someone” wouldn’t become typical of Herbie, while “The Pleasure is Mine” is both sweet and ominous, not that the juxtaposition of moods is uninteresting. The watermelon spin-off is “Blind Man, Blind Man” - jukebox monotony - and the R&B inflections of “And What If I Don’t” come off somewhat trite, even if the form of the song isn’t. The future is glimpsed in the uncommon chord progressions of “King Cobra”, not to mention the vamps within the tune and the spontaneous variations from drummer Tony Williams. It is by far the most valuable composition on the album; unfortunately, none of the soloists sound comfortable with the tune’s changes. Donald Byrd, so effective elsewhere, sounds a little out of sorts, and Hank Mobley flounders in search of standard footholds that aren’t there. Herbie’s own solo could have used another chorus to develop its ideas - hell, he should have kept all the solo space to himself. In any case, “King Cobra” is really the one track that demands to be heard again and again. In sum, My Point of View walks the listener through a gallery of possible futures for Hancock, though it leaves only a couple of lasting impressions.

The black sheep of the Blue Note bunch offers a more direct view of Herbie’s skills than the first two albums combined. Backed by Paul Chambers on bass, Willie Bobo on drums, and Oswaldo Martinez on percussion, Herbie’s piano has nowhere to duck for cover, nor does it need to. The music is mostly instant composition; there isn’t a single written melody apparent on the record. Chord changes are also out the window, except for the two-chord backdrop in the gentle “Mimosa”. What holds the music together are the insistent rhythms (vaguely afro-latin) and Chambers’ punchy basslines, over which Hancock takes off into the marquee inventions. Take “Succotash”: brushed snare and shaker nail the phonetic rhythm of the title, Chambers plucks a spare bassline, and Herbie tinkers with minor-key figures. No theme, no changes; the whole point of the piece is the interlocking of rhythms in a well-spun web. Or try “Triangle”, which morphs from themeless 4/4 swing into a superimposed 12/8 feel and back again as Hancock improvises monophonic lines on the fly. In “A Jump Ahead”, the pianist constructs his solo in response to the pedal notes that Chambers chooses at regular intervals, kind of an extended call and response game.

Inventions and Dimensions presents a free approach to jazz performance, yet Hancock and Chambers never go “out” with their improv, and rhythmically, there’s no chance of them dodging the double percussion section, who play with attractive feel. Well worth a listen, if only because it’s so different from his other Blue Notes.

A dense and somewhat dark suite, with Freddie Hubbard on cornet and Ron Carter and Tony Williams on the bottom end. Herbie plays with more eloquence than before, while his compositions (only four here) bring his writing voice into full original flower. Exhibit A is the chord maze of “One Finger Snap” that keeps Herbie and Freddie garrulous in their post-bop solos, and Exhibit B is the memorable “Oliloqui Valley” - cool bass part, forlorn cornet calls, and the release into bright swing. This is where mainstream jazz needed to be circa ’64, with one foot in tradition and one in the increasingly original scenarios available to jazzers at large. That is, as long as they were still down with ‘time and changes’.

The two other pieces mark the album’s extremes. One is the everlasting groove “Canteloupe Island”, a track that would still remain in the popular consciousness even without the dumbed-down, drum-machined remix of the ‘90s. It reminds me of “Take Five”, in that it has a minor-7th piano vamp at easy tempo (albeit in 4 instead of 5), a blues scale but not a blues form, and open solo space. And as with “Take Five”, connoisseurs who are bloody sick of it cannot blame the performance itself, which is brief, laid-back, and unassuming. More significant is the 14-minute freedom march “The Egg”, which perches on a recurring piano figure and a martial drum pattern. The players are otherwise left to their own whims and improvise in a foreboding way. It’s important that Herbie wanted to put this free-jazz flirtation on the table alongside the other tunes, at least as a statement of interest, and it releases the undercurrents of darkness in the shorter pieces.

It took me a few years to agree with the consensus verdict of this album being a classic. It brings into clear focus the best of Hancock’s tendencies: modal beauty (the title track), mysterious balladry (“Little One”), free swing (“Survival of the Fittest”), lyricism (“Dolphin Dance”), and abstract bop (“Eye of the Hurricane”). The quartet of the previous record is joined by George Coleman, who displays a clear understanding of what Hancock was after in his compositions. Some lament the fact that Wayne Shorter didn’t make this date, but Coleman’s tenor statements hold up very well. He knows exactly what to do with the open expanse of the title track - a series of suspended chords, reaching to sea and sky - and his phrasing elsewhere is very effective. “Maiden Voyage” is also a prime example of Hancock’s penchant for in-between grooves - not quite swing, not quite straight eighths. And those chords are sweet. As much as Herbie was able to mix it up as a linear player, his best jazz art is equally defined by vertical space. This also applies to the ballad “Little One”, where the sensual harmonic headroom never diminishes, not even when Freddie is steamrolling through his solo with something less than sensitivity.

The semi-frantic “Eye of the Hurricane” and the graceful “Dolphin Dance” are more within the trumpeter’s jurisdiction. The latter counts as one of Herbie’s finest compositions. Every track on this album shines in one way or another, and it is the most comprehensive of Hancock’s early efforts.

An impressionistic program for piano trio, augmented by flugelhorn, bass trombone, and flute. (I would call it a sextet, but none of the horns take solos.) Herbie has learned how to use both piano and pen as tools of seduction, and it pays off very well. The title track, one of his best works ever, is a chart of superb modulations and cushioned textures over a bossa foundation. The piano doesn’t solo so much as linger in the space set up by the exposition, and the result is a pure sonic painting, as full of detail as the electric canvases Hancock would sketch later. “Goodbye to Childhood” and “Toys” also have nice horn arrangements, and the latter veers toward a bluesy swing for the solo. Herbie revisits “Riot” and “The Sorcerer” (previously contributed to the Miles quintet) and takes provocative solos on both. These two are still interesting compositions, with or without the Dark Prince’s presence. Ron Carter contributes “First Trip”, a Monkish ambler that the horns sit out and that the trio brings to an amusing conclusion.

This significant record balances Herbie’s pastoral influences (Evanses Gil and Bill) with an acoustic vision of his electric future with Mwandishi, the polytonal synths, and so on. It seems to emanate more directly from his heart and right brain than any of his previous records, although some may argue that point.

More colors, more brushes: the emboldened leader now writes for a nine-piece (flugelhorn, two ‘bones, bass clarinet, flute, tenor sax, and piano trio) in an impressionist vein. Where Mingus would have a crew like this howling at the moon and swinging to Sunday, Hancock continues to explore the plush soundscapes established by “Speak Like a Child”. The title track has some connotation of what a big-little-medium band ought to sound like, although its jutting angles and agitated Joe Henderson solo defy expectations. More definitive of the record’s overall gist are the glowing melodies of “I Have A Dream” and “Promise of the Sun” that hang weightless over captivating charts.

The album is dedicated in part to MLK, a notion that doesn’t necessarily mesh with the emotional suggestions of the music, unless you want to use phrases like “peaceful awareness” and “quiet struggles.” Nevertheless, it is a noble tribute to the ideal of equality and transcending idiot prejudices, even if these ideas are only suggested by the song titles and liner notes. Reservations might be had with some of the performances on the album, which aren’t letter-perfect in all cases, but the occasional ensemble misalignments aren’t distracting. Objectively speaking, the album doesn’t have a lot of range, as some of the tempos and melodies blur together, and only the title track clearly defines its own space. However, within the existing range, good things happen.

Here’s a clear switch from sophisticated jazz beats to emphatic rock/funk ones, where the underlying Prisoner sextet (including Johnny Coles, Joe Henderson, Buster Williams, and Tootie Heath) is augmented at times by a few studio cats (including Jerry Jermott and Bernard Purdie). Did it take a TV show commission to make Herbie cross over like this, or would he have done it regardless? Pieces like “Fat Mama” (how about that bassline?), the title track, and a couple of others are about groove and nothing else; the horn charts and spirited solos just frost the cake. There’s nothing wrong with this instrumental R&B, whether one hears it as an urban cartoon soundtrack or not, but it seems a little too tailored to big league expectations.

Countering the foot-tappers are two tracks of oasis, one being the “Jessica” ballad that lures Herbie back to acoustic piano (he plays electric everywhere else). The main gem is “Tell Me a Bedtime Story”, a wistful piece with rich chord changes and a colorful arrangement (trumpet, trombone, flute, etc) that has a delicate feel, yet its substance packs a wallop. I think Fat Albert Rotunda, fun as it is, could ultimately be dismissed but for this track, and to some degree, “Jessica.” They’re both examples of the emotional complexity Herbie had learned to create in recent years.

The next step onward for Hancock was his most esoteric one - space fusion with a sextet of Eddie Henderson (trumpet), Bennie Maupin (reeds), Julian Priester (trombone), Buster Williams (bass), and Billy Hart (drums). Hancock sticks to electric piano with primitive effects, while the horns somehow manage to sound “electrified,” especially when the studio treats them with reverb and panned echo and the like. That’s the first credit you have to give Mwandishi; they’re a medium sized jazz band on paper, but they sound as diverse as bands that run mainly on electricity. The second credit is that Mwandishi’s musical essence is very broad. There’s a dose of the impressionism Herbie perfected in the late ‘60s, jazz/funk rhythms, and also some completely free playing. “You’ll Know When You Get There” contains the best balance of these factors, what with a sentimental exposition that speaks like a child (or tells you a bedtime story), snazzy bass and drum lines, and free solos. The softness in the playing belies the risks taken in keeping the piece afloat. “Ostinato” adds guitar and extra percussion to a nonstop 15/8 bassline, over which come snaky solos and strange keyboard decoration. Befitting the title, “Ostinato” is solely a groove-based mood, and it starts to wear thin after a while, although if any early fusion track heralds “trance jazz,” here you go.

The 21-minute “Wandering Spirit Song” starts with a peacefulness not unlike Miles’ “In a Silent Way”, then the main theme gets a bit more complicated, leading to free solos from Priester, Maupin, and Herbie. Periodically, the band returns to the main theme, which makes great use of the horns’ sonorities. Maupin’s angst-ridden bass clarinet solo is the most extreme moment on the record. Herbie takes an abstract solo with close support from Buster Williams. Both Williams and Hart are very flexible throughout, sometimes laying a foundation, sometimes playing color and counterpoint. Mwandishi overall goes to interesting places and establishes the basis for further journeys.

Crossings is the definitive Mwandishi statement and the most conceptually adventurous record Hancock ever piloted. The title of this album appropriately suggests entry into new territory, and it mirrors what was happening in progressive rock, experimenting with synths, complex textures, and long forms. To help enlarge the scope of the music, Patrick Gleeson adjuncts the band on synthesizer, while extra percussion and a wordless vocal chorus join in at key moments. The main track is the 24-minute “Sleeping Giant”. (I just realized when writing that Mwandishi’s three albums all have the same format of one sidelong piece and two pieces half that length. Just like, er, Close to the Edge.) It begins with a percussion intro and then turns to a plaintive theme that recurs at various points in the piece. Groove-backed solos subsequently take up much of “Sleeping Giant”, and in the middle is a hip detour in 13 - who says odd meters can’t be funky? For the balance of melody, space, texture, and pocket funk, “Sleeping Giant” might be the group’s best track overall. “Quasar” has the dated sound of a space movie/TV theme thanks to the high, vibrato-whistle melody and synth effects, while the intermittent funk bassline and free improv put the music in the 1972 here and now. One characteristic I’ve forgotten to mention yet is how delicate Mwandishi can be in their freeform dynamics, which can be heard in the “Quasar” intergalactic trip. “Water Torture” sounds the horns above acoustic-electric textures and a slow rhythmic procession. At times, the rhythm disappears and the group drifts into quilled ambience. The instrumental reverberations again give the impression of space, both musical and interstellar. In the closing section of “Water Torture”, muted trumpet floats above twisted Mellotron and synth tones. If you’re ever contemplating the vast mysteries of the universe, “Water Torture” might be the ideal soundtrack. Assuming the Eno records aren’t handy. I don’t think the progressive rock reference is out of line, because a lot of gray-area music broke new ground at this time. Mwandishi operates on a large scale, not necessarily to accommodate solos from everybody (they don’t follow strict soloing routines, anyway) but to create a musical journey every time out. Crossings is a transcendent success, and I think it’s one of the best early ‘70s records, regardless of artist or genre.

(The three Warners albums above are all available in a complete 2-disc set issued in 1994, and they are also available individually as remastered imports released in 2001.)

Hardly transcendent, Sextant feels empty at times, emphasizing rhythm more than ethereal sounds or forms. Switching to Columbia studios gives the band a sharper sound, and that’s about the only improvement. On “Rain Dance”, the band improvises around an electronic noise sequence - Henderson’s opening trumpet statement against this bloopy loop is quite nice - and eventually the real instruments fall away, leaving only the synthetics in a maddening trance. Indeed, this is looked back upon as early trance or acid jazz, whatever you want to call it. The ominous “Hidden Shadows” lurches along in 19, with the horn theme sounding like a slowed-down big band. I love the way Mwandishi takes on arcane metrical divisions like this, and the 19/4 is so spread out that you don’t notice the number unless you count it. Somewhere in the midst of it all, Hancock plays a reverb-drenched piano solo that sounds like McCoy Tyner transmitting a message from another planet. Great track. The main disappointment is the 19-minute “Hornets”, which would be rather tedious if it was even half that length. The “Shaft” hi-hat pattern, fuzz/wah bass, and busy keyboard is fun at first, but monotony sets in when it’s evident that the groove is never going to change, and there are no melodies or dynamics to speak of. A horn fanfare emerges at various points, yet nothing else budges to acknowledge it. So we’re left with wandering solos and miniscule beat variations. Synths whir and bleep, and there’s also a horrible kazoo-like instrument that quacks through most of the piece. It might be the “hum-a-zoo” listed in the liner notes - part duck, part buzzing hornet, part stupid. Anyway, “Hornets” goes on and on and barely gets anywhere.

I think “Hidden Shadows” is fantastic and worth the price of this midline CD reissue, but Sextant otherwise drops the ball on the group’s atmospheric reputation. Hearing it in hindsight, one can single out the trance business (which as a long-term reversed reference is kind of tenuous) along with Herbie’s future funk fusion starting to dance in the womb. (Since Headhunters was only a year away, that’s a much clearer connection.) In any case, Sextant has some hip moments but its musical EKG is mostly flat, notwithstanding a few spikes.

Satisfied that space was still the place, Herbie jettisoned all of Mwandishi save reedist Bennie Maupin and hired bassist Paul Jackson, drummer Harvey Mason, and percussionist Bill Summers to aim at funk-jazz fusion, emphasis on the former. The resulting Headhunters is one of the most popular jazz titles ever, ranking with such Columbias as Kind of Blue and Time Out as a likely album to find on even a non-jazz listener’s shelf. The main attractions are the chromatic/pentatonic funk of “Chameleon” and the bass-heavy update of “Watermelon Man”. Side 2 is no slouch either. “Sly”, ironically, has nothing to do with Mr. Stone, but is instead the most complex piece on the album, and it builds up thick steam during the solos. “Vein Melter” weaves a mood tapestry, heavy on the sustained keyboard chords. The album became its own genre, and even though there are some dull patches, no Monday morning quarterbacking could bring the music closer to its goal.

Maupin does decent sax work, and Hancock is all over the keyboards (mainly electric piano). Like Zawinul, he uses synths in expressive ways, though I’m not keen on the gimmicky solo in “Chameleon”. The real juice for me is the rhythm section, specifically in “Chameleon”. The first half of this lengthy track sticks to a repetitive bassline, while the second half changes into a sequence of jazzy chords and cadences. The way Jackson and Mason play around with the groove is just wonderful; some of my favorite drumming ever is what Mason plays in the last half of “Chameleon”. Great record overall, a must own.

Headhunters became a working band around this time, though Harvey Mason stuck to studio work and drummer Mike Clark was recruited into his place. Clark’s work with bassist Paul Jackson on this record is legendary. How about that subdivided rhythm in “Actual Proof”? Or the syncopations in the midst of the “Butterfly” tone poem? Beatwise, this stuff earns a PhD. But advanced rhythm is almost all it’s got going for it. Like Headhunters, Thrust has four pieces. The opening “Palm Grease” has quite a slick groove, and the synth-string chords that Herbie summons at the end are very cool, but in between is several minutes of monotonous jamming where the group seems to have hypnotized itself. “Actual Proof” is a bit more interactive and on the edge; Bennie Maupin plays the theme on flute, and Hancock burns up the electric piano. “Butterfly” moves Maupin to bass clarinet (and sax) for a long, lazy melody over soft rhythms and dreamlike keyboard pads. In the middle, the bass and drums double up the time, and Herbie jabs at the clavinet before soloing on electric piano. This is probably the best moment on the album, just for what the bass and drums are doing. The closing “Spank-a-Lee” (wot?) ups the energy with a serious Jackson/Clark groove and Maupin is finally turned loose on tenor sax. It’s very exciting in comparison to the slickness elsewhere.

Headhunters and Thrust are similar records; I prefer the former by a few notches, although the latter is more advanced in some ways. Bottom line is that if you dig one of them, you can’t miss the other.

Corralling a variety of names (Shorter, Maupin, drummers Mason and Clark, multiple bassists, etc.) into play, Herbie now sprays his funk-jazz with an extra gloss of fashionable pop textures, intentionally crafting Man-Child as a Record rather than taping the output of a specific band. Despite the artificially seductive entries “Sun Touch” and “Bubbles”, groovy workouts like “Hang Up Your Hang Ups” and “The Traitor” balance the funky interplay one might expect with post-meditated studio massaging. The former is catchy arrangement of multiple melodic riffs, and the latter works up a similar breadth in ultra-cool lines (particularly from the bass) and instrumental contrasts. The increasing tempo of “The Traitor” reveals a band performance at heart, upon which the overdubbed bits are smoothly layered. The electric piano solo of “Heartbeat” comes closest to jazz headiness – fluid harmonic twists of ‘60s vintage – and “Steppin’ In It” weaves the chromatic bass part of “Chameleon” into a stuttering strut, Stevie Wonder dropping in his harmonica along the way. While Man-Child has more commercial ambition than the preceding titles and is more of a ‘production’ in general, it naturally extends Hancock’s efforts at danceable rhythms and thrifty melodies topped by the occasional hip solo, and I might save some space by saying that 1976’s Secrets shares much the same approach.

(I had the cassette of Man-Child for a long time and then found a 1992 Columbia Contemporary Masters CD, which doesn’t sound as strong as later reissues like Headhunters or Thrust, but there’s always the volume knob and EQ...)

The decoy question is if Herbie had lost some of his pianistic touch after several years of electric keyboarding. VSOP suggests one answer, this album suggests another, and we’re left saying that he isn’t as subtle as he used to be. Strewth. The real issue is whether or not Hancock can carry himself by himself, because for all the circumstantial solo interludes that he played on, say, Miles’ gigs, he’s always been centered in the role of a complementary ensemble player. Though technically and musically sound, his solitaire renditions are vaguely unfulfilling, at least in comparison to solo performances by peers Jarrett and Corea, who both have the intuitive senses of drama, pace, and development necessary for the format. Consider Herbie’s take here on “My Funny Valentine”: it’s lengthy, in-depth, and investigative in the sense of someone circling a showroom car, deciding whether or not to buy. He pokes and prods it with walking bass lines, classical ripples, deconstructive runs, and tender phrases, playing with the song but not fully embracing it. It’s a fascinating track to listen to, yet the lack of something indefinable (an emotional consistency, perhaps?) nags at every brilliant bar. (Now compare this to his unaccompanied “Valentine” excerpts with Miles, and see which gets closer to the heart of things.) More emotionally direct is “On Green Dolphin St.”, in which Herbie personalizes the melody over a gentle left hand vamp, while the potentially tired choice “Someday My Prince Will Come” is given a fresh, reharmonized setting. The four originals are somewhat of a letdown after the standards. “Harvest Time” is a bit sappy, and “Sonrisa” is nice but for the distraction that it sounds like something Chick Corea might have written. “Manhattan Island” is a pleasantly oblique ballad. “Blue Otani” offers a dose of slow, funky swing. The last thing Herbie probably wanted was to make background music, and unfortunately his originals here fail to rise above that designation. They want not for impeccable execution but for that X factor of complete seduction.

The 2004 reissue comes with a few bonus tracks, including interesting retakes of the standards, and the liner notes play up the technology used in the original recording. Hancock saw it as a challenge to record both LP sides in real time, Direct to Disc, and while this is an exemplary studio recording, it’s telling that Hancock’s and the producer’s reminiscences are about these technical considerations and not the actual music. Despite some reservations, and unfair comparisons (I really don’t have any business measuring Herbie against his friends), it’s an enjoyable disc.

Rock and roll! Supergroup! Here’s the all-star conglomerate of Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, Tony Williams, and Herbie wowing two nights’ worth of Tokyo crowds with balls-out acoustic jazz. It’s mixed LOUD, too (the compression-sensitive may have to cover their ears), with Tony’s rock kit and Ron’s fat bass fueling a blunt wall of sound. The program is the same for both nights, with a couple of ‘60s tokens (“Eye of the Hurricane”, “Pee Wee”) surrounded by newer efforts, the best of which is Williams’ souped-up cop show theme, “Para Oriente”. Herbie’s “Domo” sucessfully retrofits hardbop, although Freddie’s flubbed high notes during the ensemble are painful. There is some sloppiness on both nights that may have been part and parcel of an outdoor gig for a wild throng. Ron’s intonation isn’t great, and the themes get bungled here and there, but the playing is so intense and adrenalized that these are acceptable casualties.

What the listener really wants is the interplay that these guys are renowned for, and there’s a fair amount on both discs - dial up the first night’s “Pee Wee” for one example. The approach to the tunes changes from night to night. The first “Hurricane” is merciless, with Tony whipping up something obscene under Freddie’s solo, then on the second night, the drummer suddenly lays out, leaving Wayne with an unaccompanied spot. “One of Another Kind” has a climactic drum feature in one version but not in the other. And so on. The solos are all post-post-modern bop dispatched with demigod chops. Peeves: Wayne’s soprano sounds like a dog toy (he’s mostly on tenor), Herbie is sometimes at a loss and just wipes up and down the keys, and Ron is Mr. Slide - I cringe at every one of those goofball, crowd-teasing fretboard slides in “Fragile”. This isn’t the place to hear these players re-capturing their 1960s subtleties - Tony’s thunder makes sure of that - but it’s a strong double dose of energy nonetheless. The set ends with Herbie and Wayne trying to get intimate with “Stella By Starlight” and “On Green Dolphin St.” amidst an overly vocal coliseum. Shut up already and let them play. What is this, a sport?

Columbia/Sony picked up Herbie just as he was finishing with Mwandishi and preparing to git funky with Headhunters, a band that gradually dissipated as Herbie slid closer to straight disco and R&B. Lest good old acoustic jazz be forgotten, Herbie also assembled the VSOP band smack in the middle of his electric endeavors. By the ‘80s, the new synth technologies were too tacky to ignore, so out came drum-machine and sampler tapestries like Future Shock, Sound System and 1988’s Perfect Machine, where this collection stops. And so, speaking of Hancock’s “Columbia Years” doesn’t really signify anything, as Herbie twiddled his fingers in lots of pies, some of them commercially flavored. Therefore this 4CD set can’t help but be very eclectic, if not schizophrenic. The Proper Acoustic Jazz on the first two discs involves the supergroup of Hancock, Hubbard, Shorter, Carter, and Williams. The quintet generates undeniable excitement - they play the hell out of almost every tune - but they miss the subtlety they had ten years earlier (under Miles, minus Freddie), arguably their defining characteristic. Even when the piano trio jams alone (“Dolphin Dance”, “Milestones”), they romp aggressively. Accepting that, a real treat from the VSOP quintet is the previously unreleased live version of Hubbard’s “Red Clay”, which jacks up the tempo and rocks out. And the majestic version of “Maiden Voyage” is wonderful. Elsewhere on the first two discs is an appearance by jazz savior Wynton Marsalis (no comment) and an impressive piano duet with Chick Corea (“Liza”). Oh, and there’s “Round Midnight” with Bobby McFerrin, who sounds so much like a muted trumpet that people who get scared by his wacky vocals (like me) have nothing to fear. The acoustic stuff amazes at times, but I would trade the lot of it for just one of Hancock’s better Blue Notes. Sure, Herbie had gotten better as a player - how could he not - but the intervening years of Fender Rhodes and Clavinets and ARPs had affected both his piano touch and style. No longer precious with notes and phrases; he goes for a broader tension and release with lots of flashy diversions. The solo Piano album reviewed above is an exception, as Hancock sounds quite elegant on it, but I still find a lot of VSOP’s work rather brutish. The second half of the collection draws from Hancock’s electric fusions. Mwandishi gets one track and Headhunters has a few, and as these were working bands, their music is the most solid of Discs 3 and 4. Other pieces like “Spider” and “Sun Child” explore the typical phased sounds and disco dialects of its time. I like this stuff in a nostalgic way, though the improvisational elements take a backseat, if they’re not stuffed in the trunk altogether. An exception would be “4 a.m.”, a stimulating funk piece featuring bassist Jaco Pastorius. (The liners list Tony Williams as the drummer for “4 a.m.”, but that’s ridiculous; it’s Harvey Mason, isn’t it?) With the addition of lame vocals to a couple of tracks, Herbie becomes an R&B artist, no better or worse than anyone fully devoted to the genre, and with a wider harmonic palette, I suppose. Somewhere in here is the instrumental theme for “Death Wish”, pure 1970s with the swirly electric piano and moody strings, and I dig it. With Future Shock (1983), drum machines replaced real rhythm sections. “Rockit” remains the automated flagship of this period, and it’s good fun, minus the dated turntable section. Sound System (1984) unabashedly reprised the popular Future Shock to a large degree, yet it also featured the original “Karabali”, where piano, percussion, a vocal chant, and Wayne Shorter’s soprano sax all blend into a stirring world-jazz pastiche. “Maiden Voyage” circa 1998 gets redone by synths, coupled with a children’s theme called “P. Bop”. What to say? Sometimes the toys get the best of us. You could probably get Herbie to play any keyboard, however cheesy, if you could convince him it just came off the assembly line, yet those electrified Maiden Voyage chords still give me goosebumps. Strange world. So who is this boxset aimed at? With more eclecticism than most, it’s one collection where the lovely and the loathsome might sit equally. Determining which is which depends on the listener’s tastes. Some tracks are classics; some are novelties; some are rare. Headhunters aside, I don’t think this was an artistically significant time for Hancock, although it certainly was fertile, and this collection samples a large variety of which “Jazz” describes only half.

(When first released, the box was literally a box - a plastic cube with four CDs and a booklet suspended on slots within. One careless move, or one misaligned disc, and all would tumble to the floor. It was the most ridiculous, impractical packaging I’d ever run across. Eventually, Columbia reissued it as a long box, and I swapped out my super special cube for it. That’s the first time I ever made a trade to upgrade the packaging.)

|